More than 12,000 confirmed cases of Oropouche virus disease have swept through 11 countries in the Americas during 2025, marking the largest outbreak in history—yet the mosquito-borne illness remains virtually unknown to most Americans despite over 100 U.S. travelers contracting the virus.

The outbreak has already claimed at least five lives in Brazil and caused birth defects including microcephaly in multiple infants—revelations that echo the devastating Zika virus crisis of 2015-2016. Unlike Zika, however, Oropouche has received minimal media coverage despite vertical transmission from mothers to fetuses being documented for the first time during this outbreak.

Historic Scale of Under-Reported Outbreak

Between January and August 2025, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) reported 12,786 confirmed Oropouche cases across the Americas—nearly matching the entire 2024 total of 16,239 cases in just seven months. Brazil accounts for 11,888 cases concentrated in Espírito Santo (6,322 cases) and Rio de Janeiro (2,497 cases), representing a dramatic surge in a disease that historically caused sporadic outbreaks of a few hundred cases at most.

The virus has now been detected in areas where it was never previously endemic, including Cuba with 28 cases, Panama with 501 cases, Peru with 330 cases and Colombia with 26 cases. Travel-associated cases have appeared in Canada, and the United States and Europe, travelling back from Cuba and Brazil, signaling the virus’s capacity to spread internationally.

United States Cases Climb to 109

As of September 30 2025, 109 Oropouche cases have been reported in 7 states among U.S. travelers returning primarily from Cuba, with Florida documenting the highest number of 103 cases. Most concerning, 2 Neuroinvasive cases being reported with Wisconsin reporting the first neuroinvasive Oropouche case in U.S. history, involving a patient who developed meningitis after travel to Panama.

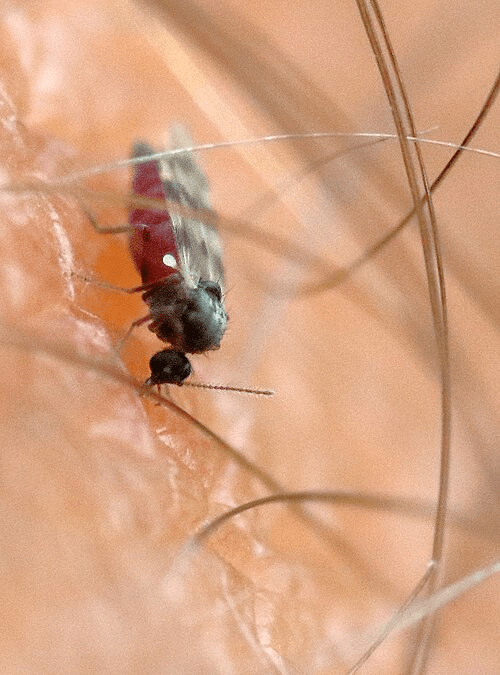

Dunpharlain, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0

via Wikimedia Commons

While no local transmission has occurred in the continental United States, Culicoides paraensis biting midges, the primary vector for carrying Oropouche virus—has low but established presence in tree holes throughout the southeastern and midwestern United States.

The Invisible Vector: Prevention Challenges

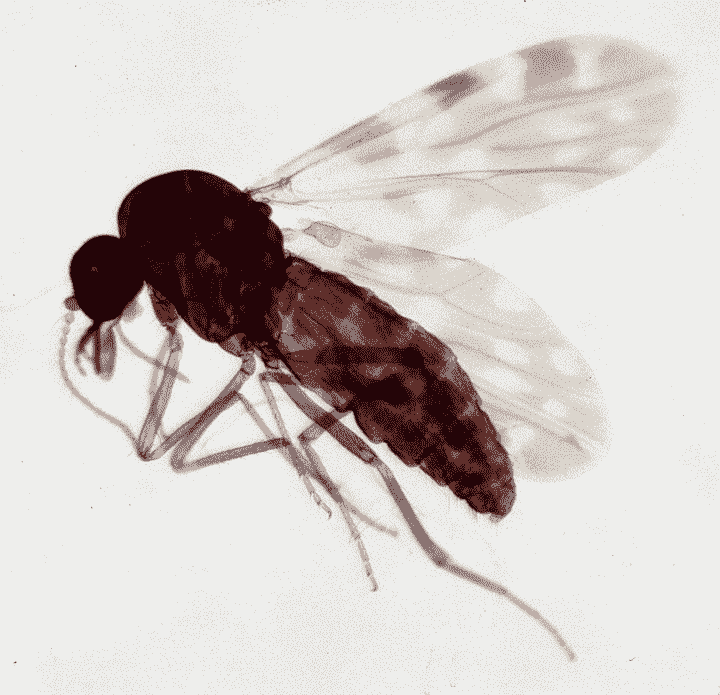

Unlike Zika and dengue transmitted by visible mosquitoes, Oropouche virus spreads primarily through Culicoides paraensis—microscopic biting midges measuring only 1 millimeter that are nearly invisible to the naked eye and can pass through standard window screens. These “no-see-ums” breed exclusively in wet tree holes throughout forests from the southeastern United States to Argentina, making source reduction impractical and traditional mosquito control largely ineffective. The midges bite primarily during late afternoon hours (4-6 PM) rather than dawn or dusk, further complicating control efforts.

The CDC recommends travelers use EPA-registered insect repellents containing DEET, IR3535, or icaridin (though effectiveness against midges is limited), wear long-sleeved shirts and pants during peak biting hours, install fine mesh screens (20×20 or finer) on windows and doors, and use fans to create air currents that blow away the tiny insects. CDC also notes that It is possible that Oropouche virus might spread through sex, but it has not yet been reported and recommends travelers consider using condoms or abstaining from sex for six weeks after returning from affected areas.

Acarologiste, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0

via Wikimedia Commons

First Confirmed Deaths and Birth Defects Shock Medical Community

The 2024-2025 outbreak shattered Oropouche’s long-standing reputation as a self-limiting febrile illness when Brazil confirmed five deaths directly attributed to the virus—the first confirmed Oropouche fatalities in the disease’s documented history. Previous medical literature described the virus as causing “rare mortality,” making these deaths particularly alarming to infectious disease specialists.

Even more disturbing are reports of vertical transmission causing severe birth defects. In June 2024, researchers identified viral RNA in a stillborn infant whose mother experienced Oropouche symptoms at 30 weeks gestation. Subsequently, four infants with microcephaly tested positive for Oropouche IgM antibodies, and one infant died at 47 days of life with multiple tissues testing positive for viral RNA.

Brazil is also investigating multiple cases of meningitis and encephalitis potentially linked to Oropouche infection, adding to concerns about the virus’s neurological complications.

Novel Symptoms and Potential Sexual Transmission

Unlike most arboviral diseases, Oropouche exhibits a troubling pattern of symptom recurrence affecting up to 70% of patients within days to weeks after initial recovery. Patients experience fever, severe headache, joint pain, and muscle aches that resolve only to return repeatedly—a unique feature that significantly increases the disease burden.

Adding to transmission concerns, researchers documented Oropouche virus RNA in semen at days 16, 32, and 58 after symptom onset, with culturable virus recovered on day 16. While no confirmed cases of sexual transmission exist, the CDC now recommends travelers consider using condoms or abstaining for six weeks after potential exposure—guidance reminiscent of Zika virus protocols.

Why This Outbreak Remains Invisible

Several factors explain why an outbreak of this magnitude has escaped mainstream attention:

Diagnostic Confusion: Oropouche symptoms are clinically indistinguishable from dengue, chikungunya, Zika, and malaria. Most healthcare systems test for dengue first, and without specific arbovirus panel testing, Oropouche cases are frequently misdiagnosed. This diagnostic challenge has likely led to significant underreporting of actual case numbers.

Overshadowed by Dengue: The outbreak coincides with an unprecedented dengue epidemic affecting the Americas, with over 13 million dengue cases reported since late 2024 and High number of cases being reported in 2025. Dengue’s established public health infrastructure and higher profile have overshadowed the emerging Oropouche threat.

Limited Research History: A bibliometric analysis published in October 2024 revealed only 148 research publications on Oropouche virus between 1961 and 2024—averaging just 2.3 papers annually. This paucity of research translates to minimal scientific infrastructure for studying or communicating about the disease.

Novel Genetic Reassortment Raises Concerns

Evidence suggests the 2023-2025 outbreak involves a novel reassortant Oropouche virus lineage with genetic recombination between different virus strains. This reassortment may explain the virus’s unprecedented clinical features, including deaths, birth defects, and expanded geographic range.

The World Health Organization conducted a risk evaluation in June 2025, concluding that two main lineages/ reassortants have been described so far: BR-2015-2024- circulating in Brazil and Cuba, and PE/CO/EC-2008-2021- circulating in Peru and Ecuador. Colombia has reported both reassortants. The identification of co-circulating strains of OROV lineages exemplifies the evolving nature of

orthobunyaviruses and raises concerns about within-species future reassortment events and emergence of

new lineages having more severe clinical phenotypes and enhanced vector competence.

Public Health Response Inadequate

Despite the outbreak’s scale, the global health response has been limited. PAHO has emphasized the need to “strenthen surveillance and vector control across Americas” and detect the virus’s introduction into new areas, acknowledging that current surveillance is inadequate.

Vector control efforts remain fragmented. Unlike dengue and Zika, which prompted large-scale Aedes mosquito control campaigns, Oropouche’s primary vector—the biting midge Culicoides paraensis—receives minimal targeted intervention despite PAHO recommendations to eliminate breeding sites through vegetation clearing.

Looking Ahead

The Oropouche outbreak demonstrates that more than 12,000 confirmed cases, five deaths, and birth defects can occur across 11 countries with minimal public awareness when diseases primarily affect lower-income regions. Prevention currently relies entirely on avoiding bites from nearly invisible midges—a challenge that has allowed the virus to spread unchecked. Health officials emphasize the urgent need for enhanced surveillance systems, expanded diagnostic testing, and coordinated research efforts to prevent Oropouche from becoming permanently established across the Americas, particularly as 109 U.S. cases signal the virus’s potential to reach travelers and potentially establish transmission in new territories.

Additional Resources:

Health officials urge travelers to endemic areas to use insect repellent, wear long sleeves and pants, and seek medical attention if fever develops within two weeks of travel.