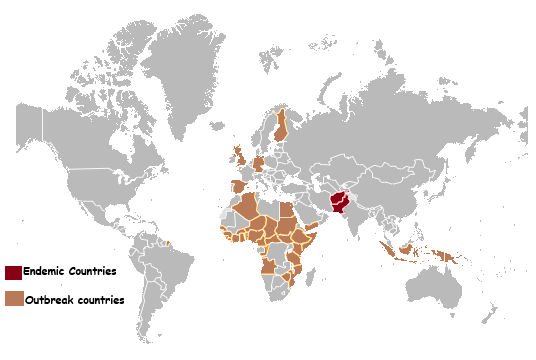

Synopsis: The latest case reports from Pakistan and Nigeria underscore the fragility of global polio eradication efforts despite a 99% reduction in cases since 1988. Pakistan’s 29 wild poliovirus cases through October 2025 continue the country’s struggle with endemic transmission, while Nigeria battles 35 vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 cases. The challenge extends beyond endemic countries: vaccine-derived strains caused paralytic cases in New York (2022) and circulated in London’s wastewater (2022), while Israel’s August 2025 environmental detections demonstrate how poliovirus can spread even in highly vaccinated populations. India maintains its polio-free certification despite detecting a vaccine-derived poliovirus case in Meghalaya in August 2024, with robust surveillance systems preventing community transmission. These developments highlight that even polio-free nations remain vulnerable amid rise in vaccine-derived polio virus strains.

Both Pakistan and Nigeria reported three new polio cases each in the first week of October 2025, intensifying concerns about the global campaign to eradicate the crippling disease despite decades of progress.

Pakistan’s three new wild poliovirus type 1 (WPV1) cases were detected in Sindh province, with paralysis onsets in August, while Nigeria confirmed three circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 (cVDPV2) cases from Borno, Kebbi, and Zamfara states with paralysis onsets in May and July. The simultaneous case reports from both countries underscore the fragility of eradication efforts and the distinct challenges each nation confronts.

Pakistan’s Wild Poliovirus Crisis Intensifies

Pakistan has now recorded 29 confirmed wild poliovirus type 1 cases in 2025 following the latest October detections, with cases continuing at concerning pace despite the country reporting 74 cases throughout 2024. The South Asian nation remains one of only two countries globally, alongside Afghanistan, where wild poliovirus transmission has never been interrupted.

All three cases reported in early October involved patients in Sindh province, the same region that has emerged as a significant transmission hotspot this year. The 29 cases are distributed across four regions: 18 cases in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP), 9 in Sindh, 1 in Punjab (Mandi Bahauddin), and 1 in Gilgit-Baltistan (Diamer district).

The most recent cases confirmed in late September before the October detections involved two young girls from Badin and Thatta districts in Sindh. Environmental surveillance reveals even broader viral circulation, with 71 WPV1-positive wastewater samples detected in the first quarter of 2025 alone, compared to just 9 from Afghanistan during the same period. These environmental detections indicate widespread community transmission even in areas without reported paralytic cases.

Security threats compound the public health crisis. Since the 1990s, more than 200 polio workers and their police protectors have been killed in targeted attacks, particularly in former militant strongholds in northwestern Pakistan. In February 2025, gunmen killed a police officer protecting a vaccination team in Jamrud district, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

Pakistan has responded with aggressive immunization campaigns, including a sub-national effort in September 2025 that reached nearly 21 million children across 88 districts. A nationwide door-to-door campaign scheduled for October 13-19 will target approximately 45.4 million children under age five, mobilizing over 400,000 frontline health workers. The campaign timing is critical following the October case detections, as health officials work to rapidly boost immunity levels across vulnerable populations.

Nigeria Confronts Vaccine-Derived Poliovirus Epidemic

Nigeria’s three new cVDPV2 cases reported in early October 2025 brought the country’s yearly total to 35, representing a significant decline from the 98 cases reported throughout 2024. However, Nigeria still faces a substantial vaccine-derived poliovirus burden that requires sustained intervention.

The October cases were detected in Borno, Kebbi, and Zamfara states—all located in Nigeria’s northwest and northeast regions where cVDPV2 transmission remains most intense. These areas overlap with the Lake Chad Basin, where operational difficulties, insecurity, inaccessibility, and climate-related disruptions allow poliovirus to persist among under-immunized populations.

Nigeria achieved a scientific breakthrough in February 2025 when the WHO genomic sequencing laboratory in Ibadan received accreditation, making Nigeria one of only three African countries capable of independently sequencing poliovirus. The facility completes sequencing within four days after receiving virus isolates, compared to weeks-long delays when samples had to be sent to the CDC in the United States.

Understanding Vaccine-Derived Poliovirus

Vaccine-derived poliovirus originates from the weakened live virus in oral polio vaccine, which can genetically mutate when circulating in communities for extended periods—typically 12 to 18 months—eventually reverting to a form capable of causing paralysis. This occurs when the vaccine virus passes from one unvaccinated child to another, accumulating mutations that restore neurovirulence.

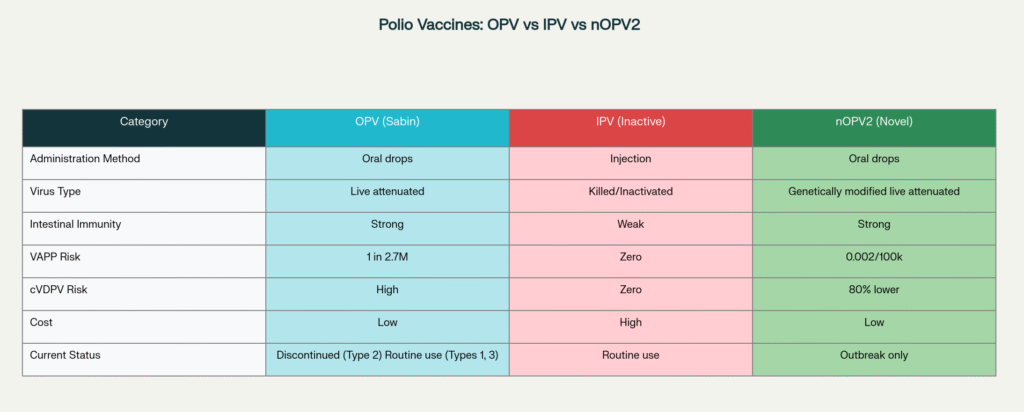

Vaccine-derived poliovirus remains extremely rare despite widespread oral polio vaccine use. Since 2000, more than 10 billion OPV doses have been administered to nearly three billion children worldwide, resulting in just over 1,000 cases of vaccine-associated polio paralysis (VAPP) during that entire period. However, circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2(cVDPV2) has become increasingly prevalent, with 65 of 67 total cVDPV cases globally in 2025 being type 2. The African region shows encouraging downward trends with 52 cases in 2025 compared to 312 in 2024 and 529 in 2023, though Nigeria’s continued case reports demonstrate persistent transmission in specific high-risk zones.

There are three main categories of vaccine-derived poliovirus. Circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV) occurs when the mutated virus spreads within communities with low immunization rates, warranting public health outbreak response. Immunodeficiency-related vaccine-derived poliovirus (iVDPV) affects individuals with rare immune deficiency disorders who cannot clear the vaccine virus from their intestines, leading to prolonged excretion—only 200 cases have been documented worldwide since 1962. Ambiguous vaccine-derived poliovirus (aVDPV) refers to cases where the virus is found in individuals without immunodeficiency and is not circulating in the community.

Global Switch from Trivalent to Bivalent OPV

In April 2016, the world achieved an unprecedented public health milestone when all 155 countries using oral polio vaccine simultaneously switched from trivalent OPV (tOPV) to bivalent OPV (bOPV) in a globally coordinated effort. This historic switch removed the type 2 component from oral polio vaccines after wild poliovirus type 2 was declared eradicated in September 2015—the last case having been detected in 1999.

The primary rationale for discontinuation was that type 2 circulating vaccine-derived polioviruses (cVDPV2) had accounted for more than 94% of all cVDPV cases detected between January 2006 and May 2016, causing hundreds of paralytic poliomyelitis cases despite the absence of wild type 2 virus. The type 2 component also accounted for 40% of vaccine-associated paralytic polio (VAPP) cases annually. To mitigate risks associated with declining type 2 immunity after the switch, the World Health Organization recommended that all countries introduce at least one dose of inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) into their routine immunization schedules, which protects against all three poliovirus types without risk of vaccine-derived transmission.

This phased withdrawal strategy represents the first stage toward eventual cessation of all oral polio vaccine use once wild poliovirus types 1 and 3 are also eradicated globally. However, a genetically modified novel OPV2 (nOPV2) introduced in 2021 continues to be used exclusively for outbreak response in areas with active cVDPV2 transmission, as it provides superior intestinal immunity compared to IPV while carrying significantly lower reversion risks than traditional Sabin OPV2.

Novel OPV2 Introduction: A Pragmatic response to a challenging Paradox

The introduction of nOPV2 represents a pragmatic response to a challenging paradox: using an improved live vaccine to control outbreaks caused by mOPV2 vaccine-derived virus. Traditional Sabin OPV2, originally contained within trivalent OPV until 2016, had caused 94% of all vaccine-derived polio outbreaks and 40% of VAPP cases globally despite successfully eradicating wild poliovirus type 2. Even after its removal from routine immunization, the monovalent OPV2 (mOPV2) that was used to respond to cVDPV2 outbreaks continued to seed new cVDPV2 emergences, creating a vicious cycle where the outbreak response tool was perpetuating the problem it aimed to solve. Hence nOPV2 with genetic engineering improvement was introduced. nOPV2 promises to break the vicious cycle of creating new cVDPV emergences while responding to cVDPV2 outbreaks While this approach may seem contradictory, the substantially lower reversion risk of nOPV2 breaks the cycle of continuous cVDPV2 seeding, providing a pathway toward eventual cessation of all oral polio vaccines once transmission is fully interrupted.

As of 2025, approximately 1.65 billion nOPV2 doses have been administered across 35 countries, with only 30 cVDPV2 emergences associated with nOPV2 use—a substantially lower reversion rate than traditional Sabin OPV2. While nOPV2 is not used for routine immunization, it remains an essential tool for controlling outbreaks in under-immunized communities where inactivated polio vaccine alone cannot stop intestinal transmission.

now use multiple strategies to combat both wild and vaccine-derived poliovirus.

Previous Vaccine-Derived poliovirus type 2 outbreaks

United States Detects Vaccine-Derived Polio in New York

On July 21, 2022, the United States reported its first paralytic polio case in nearly a decade when a 20-year-old unvaccinated adult in Rockland County, New York developed paralysis caused by vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 (VDPV2). The patient had not traveled internationally, indicating community transmission within the United States. Extensive wastewater surveillance between April and August 2022 detected poliovirus in 101 environmental samples across multiple counties including Rockland, Orange, Sullivan, Nassau, and New York City, revealing sustained silent transmission over several months. The World Health Organization classified it as circulating VDPV2 (cVDPV2) on September 13, 2022, with genome sequencing identifying genetic links to VDPV2 detected in Israel, United Kingdom, and Canada.

United Kingdom Responds to London VDPV2 Detection

In February 2022, the United Kingdom initiated a national enhanced incident response after routine environmental surveillance persistently detected vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 (VDPV2) in sewage samples from London’s Beckton treatment works, which serves nearly 4 million people across north-east and north-central London. The virus continued evolving over subsequent months, and in August 2022, the World Health Organization formally confirmed the UK had a circulating VDPV2 (cVDPV2) outbreak based on sustained detection for over 60 days. Genetic analysis revealed the virus was linked to VDPV2 detected in Israel and the United States, demonstrating transnational spread through international travel.

Despite over 100 infectious poliovirus isolates obtained from wastewater samples between February and November 2022, no paralytic polio cases were identified throughout the outbreak. The UK Health Security Agency launched an emergency inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) booster campaign in July 2022 targeting all children aged 1-9 years in London, delivering more than 370,000 booster doses by December 2022. The last environmental detection occurred in early November 2022, suggesting the vaccination campaign successfully interrupted transmission. The WHO removed the UK from the list of polio “infected” countries in December 2023 after 12 consecutive months with zero detections, though a community stool survey of over 1,000 children conducted from October 2022 to April 2023 found no evidence of poliovirus infection, indicating the outbreak remained subclinical despite sustained environmental circulation.

previous vaccine-derived poliovirus type 1 outbreaks

Israel Reports Unexpected Outbreak

Israel declared a circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus type 1 outbreak in August 2025 after detecting nine genetically related isolates in wastewater samples between February and July 2025. The samples came from seven sites across four geographically non-overlapping areas in Jerusalem district and Central Region, indicating sustained community transmission.

No paralytic cases have been reported, though a 17-year-old unvaccinated male from Jerusalem developed vaccine-associated paralytic poliomyelitis in December 2024. Israel discontinued routine bivalent oral polio vaccine (bOPV) use in March 2025 but maintains four doses of inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) with 98% national coverage, though Jerusalem’s vaccination rates fall notably below WHO-recommended thresholds.

India’s Meghalaya VDPV1 Detection

India remains polio-free since its last wild poliovirus case in 2011, with strategies pioneered in India now being deployed in Pakistan and Afghanistan. India primarily uses two types of polio vaccines: the Inactivated Polio Vaccine (IPV), given as an injection, and the Bivalent Oral Polio Vaccine (bOPV), administered as drops in the mouth. IPV contains inactivated (killed) polioviruses, providing a strong systemic immune response. Bivalent Oral Polio Vaccine (bOPV) contains weakened (attenuated) polioviruses of types 1 and 3, which induce an immune response without causing disease.

India’s acute flaccid paralysis surveillance system in August 2024 detected a vaccine-derived poliovirus type 1 (VDPV1) case in a 2.5-year-old child from West Garo Hills district in Meghalaya. Initial reports classified the case as immunodeficiency-related vaccine-derived poliovirus (iVDPV), but follow-up testing by ICMR-NIV subsequently confirmed that the child’s immunological profile was normal and the child was not immunocompromised. The polio was caused by the live, weakened type-1 virus strain from bivalent oral polio vaccine that had mutated and regained neurovirulence in a child who was not fully immunized. Surveillance confirmed no evidence of virus circulation in the community, meaning it was not classified as circulating VDPV (cVDPV) but rather Ambiguous vaccine-derived poliovirus (aVDPV). The case reignited debates about India’s continued use of oral polio vaccine alongside inactivated polio vaccine.

This case does not affect India’s polio-free certification, as sporadic vaccine-derived cases occurring without sustained community transmission do not compromise a country’s certification status.

The Bottom line

The 42nd meeting of the WHO Polio IHR Emergency Committee in June 2025 reaffirmed global targets of interrupting and certifying WPV1 eradication by 2027 and cVDPV2 elimination by 2029. However, the continued case reports from Pakistan and Nigeria in October 2025 highlight the substantial challenges remaining to achieve these ambitious goals.

As the global community approaches the final stages of this decades-long campaign, maintaining vigilance in polio-free countries while intensifying efforts in endemic regions remains critical. The cost of failure—ongoing paralysis of children, potential reintroduction to polio-free regions, and wasted billions in eradication investments—far exceeds the resources needed to eradicate Polio. Only through collective resolve can the world deliver a polio-free future for generations to come.