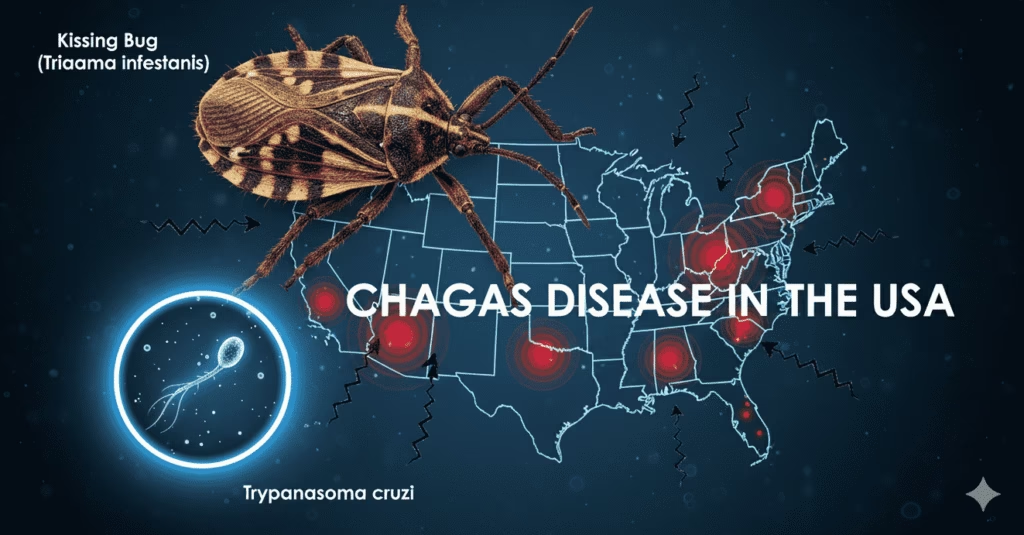

Chagas disease, a parasitic infection historically confined to Latin America, has now established a silent but growing presence in the United States, raising public health concerns. Known as American trypanosomiasis, the disease is caused by the Trypanosoma cruzi parasite, primarily spread by triatomine insects commonly called “kissing bugs” due to their tendency to bite around the mouth and eyes.

Recent research published in the CDC journal Emerging Infectious Diseases reports human cases in eight US states, including California, Texas, Florida, and Arizona. The study recommends classifying Chagas disease as endemic across these regions—a status that acknowledges its continuous presence and encourages expanded monitoring and research.

Dr. Norman Beatty, lead author of the CDC study, explains that the kissing bugs transmit the parasite by feeding on human blood and depositing infected feces near the bite site, which allows the parasite to enter through the skin or mucous membranes. While often asymptomatic during the acute phase, the disease can progress silently for years, potentially causing severe cardiac and digestive system complications such as heart failure and gastrointestinal issues.

In Texas alone, more than 50 locally acquired human cases were reported between 2013 and 2023, with infection rates among dogs in some kennels as high as 31%. Experts emphasize that the disease’s silent nature poses a significant risk, often going undiagnosed until serious symptoms emerge.

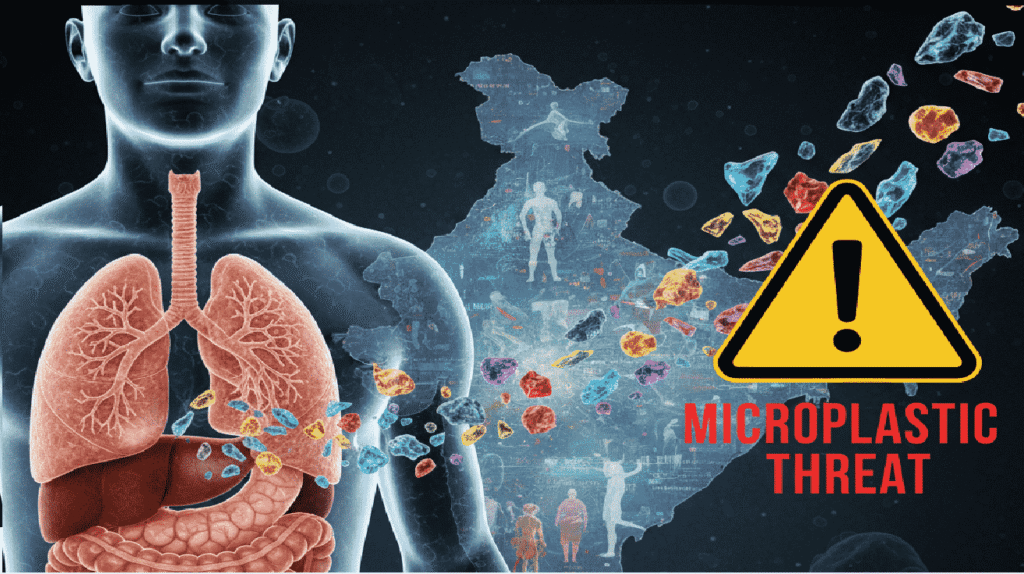

The global spread of Chagas disease correlates with factors such as increased travel and migration from endemic regions, urbanization that alters insect habitats, and non-vector transmission routes including blood transfusions, organ transplants, and congenital infections.

In India, reported cases of human Chagas disease are extremely rare. Though a few cases of animal trypanosomiasis have been noted, human infections remain negligible, and the disease is not currently considered a public health threat. Medical experts urge travelers and healthcare professionals to maintain awareness because of growing global interconnectedness.

Preventing Chagas Disease: Expert Advice

- Currently, there are no vaccines or medicines to prevent Chagas disease, so prevention focuses on avoiding contact with kissing bugs and minimizing transmission risks. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends staying in well-built or screened accommodations, especially when traveling to endemic areas. Using insecticide-treated bed nets, wearing protective clothing, and applying insect repellents on exposed skin can reduce exposure.

- Proper home maintenance is also critical—sealing cracks and gaps in walls and roofs, repairing window and door screens, and removing brush or wood piles near residences reduce bug habitats. Indoor insecticide use and improved housing quality have proven effective in endemic regions to lower disease rates.

- Screening blood donations and organ transplants for Trypanosoma cruzi is a vital prevention strategy to avoid transmission via medical procedures. Pregnant women from endemic areas should be tested to prevent congenital infections, and prompt treatment of newborns significantly reduces complications.

- Additionally, practicing good food hygiene, avoiding unpasteurized juices or improperly prepared foods, and maintaining insect-free environments in food production are recommended to avoid accidental oral transmission.

World Chagas Disease Day, observed every April 14, highlights the critical need for awareness, early detection, and equitable access to care worldwide, as the disease continues to pose challenges beyond its traditional borders.

Treatment options remain limited, with only two primary antiparasitic drugs—benznidazole and nifurtimox—available for early-stage infections but not yet FDA-approved in the US. Research continues toward more effective therapies.

As Chagas disease gains recognition as a significant health challenge beyond its traditional boundaries, public health officials stress the importance of awareness, early detection, and collaborative research efforts. The experiences in the US may serve as lessons for other countries to remain vigilant and prepared for emerging infectious threats.